It was the elephants that first caught my attention. I was meandering through the Spitalfields area of London this morning after church, enjoying the relaxed, happy atmosphere that often seems to fill the streets of big cities on a sunny Sunday morning. As I passed through a plaza between two enormous office buildings, I saw several sculptures of elephants and thought I’d take a look.

It turns out that each sculpture is a replica of an actual elephant who was rescued, and each one stands (or sits) above a plaque that gives its name, date of rescue, and the reason it needed to be rescued in the first place.

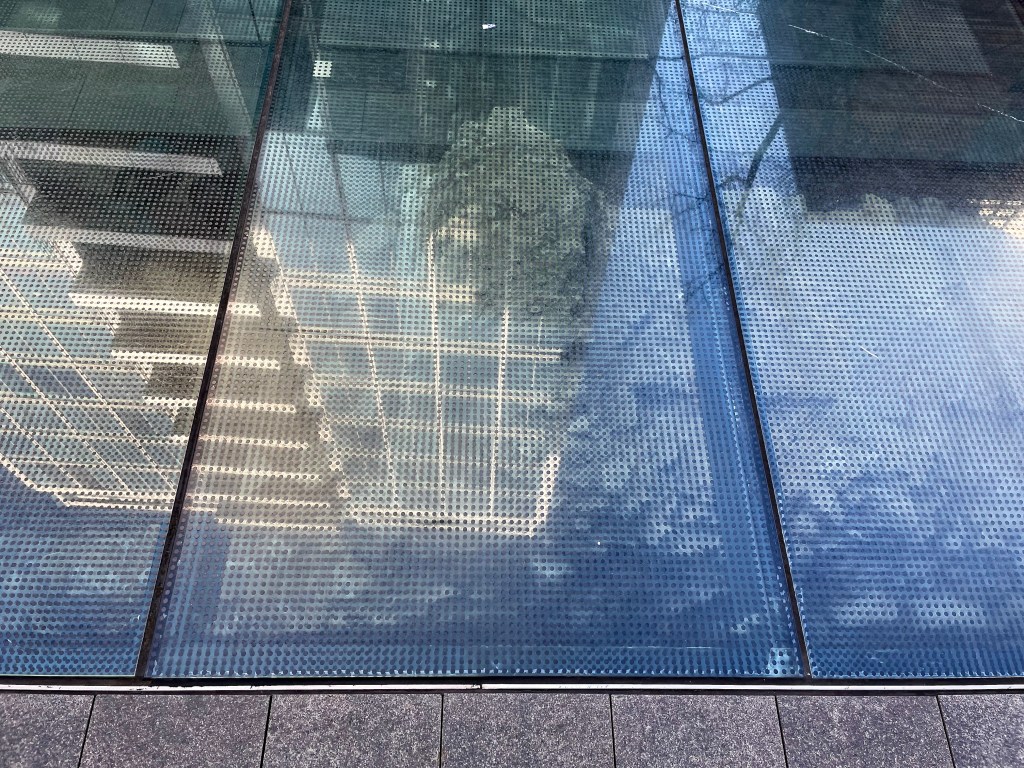

As I crossed the plaza, however, I realized that I was walking on a glass floor, and beneath the glass were—old stone ruins! I looked all around for a plaque and couldn’t find one. I tried to guesstimate based on the stones I saw. Roman?

Then I noticed that there was another courtyard several feet below ground level, and when I walked down there, I discovered a window that made the ruins visible from the side, along with a plaque explaining that they had originally been a fourteenth-century Charnel House (so my guess had been exactly right, give or take a thousand years). A charnel house was a place to store bones that had become unearthed digging other graves. This one would have held the final remains of hundreds of people who had died in a great famine.

The walls were discovered only in 1999, and the plans for the surrounding buildings were adapted to rescue the ruins—the whole plaza is apparently a rescue operation—and make room for this display. The two sculptures in the ruins, by David Teager-Portman, were added in 2014.

I had a heavy heart as I looked into the past through those panes of glass, partly because I was staring at what had effectively been a mass grave, and partly because the sculptures somehow made the enclosed scene seem sad and suffocating.

In large part, however, I felt heavy because I’ve been thinking about what the students and I will make of our past in Britain, and my fear is that our experiences, learning, and wisdom will be sealed off in a way that enables us to walk right over top them. What does it mean that we were all here? What connection will our recent past have to our ever-emerging presents? Once the past goes into our pockets, will we forget it’s there?

I kept a blog when I directed this program in 2018. I wrote a lot. I’ve never re-read a single entry.

A couple of weeks ago, I asked students what about their experience here they wanted to keep, and then I asked them which specific actions they’d have to take in order to keep those things, because otherwise good intentions will evaporate on the return flight over the Atlantic Ocean, and present realities back home will quickly seal off habits and practices from our time in Britain.

My hope is that the Semester in Britain becomes something more than a pocket for our learning, more than a glass case in which our experiences are preserved by being frozen, and quite possibly ignored. I would prefer the gains we’ve made here—and several students have made great gains, indeed, judging by their final portfolios—to grow organically into our ongoing lives, not to fall into some safe, protective space.

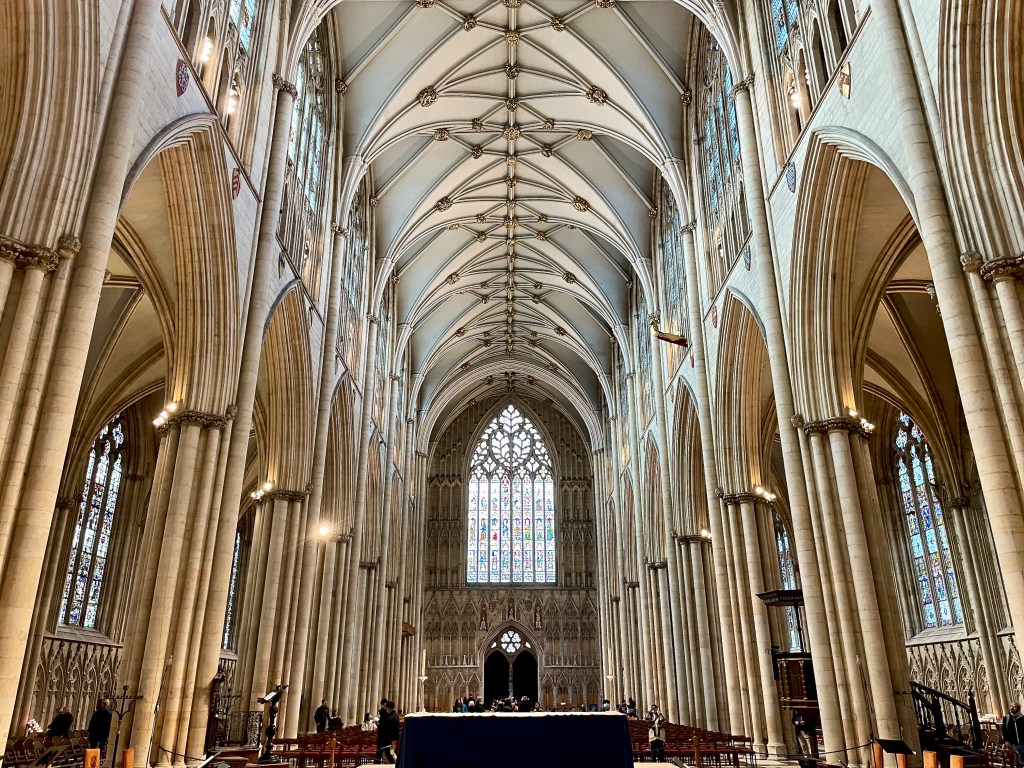

Leaving the plaza, I looked down the road to see the church I had attended this morning, Christ Church Spitalfields (CCSpits for short), a hulking eighteenth century church that dominates the local area.

The church runs three services each Sunday, a lively one at 5:00pm for young people; one for families at 11:00am; and one for guys like me: the 9:00am service strictly follows the old Book of Common Prayer, with music on the pipe organ.

It had been a strange service. Make no mistake: the language was exactly what I had come for: straight-up old school Anglican. No eye-rolling or irony about any of it. If you closed your eyes and only heard the service, it could have been from any time in the last few centuries. I have been looking for that worship experience, without success, since my first Sunday in Liverpool.

But I was one of only a dozen congregants, including a handful of regulars. The priest was young, sturdily built, with a bald head and full beard—I would have guessed that he brewed his own beer—wearing the traditional black clerical shirt and white collar with a tweed coat over jeans and Doc Martens. He was calm but charismatic, having a quiet conversation with each newcomer before the service. He looks you right in the eye when he talks and listens.

The setup was slick: large screens so that everyone could see, with lyrics to songs on all three of them and different images—e.g., shots of the organist’s hands—sometimes appearing on some of the screens. Someone behind the scenes was clearly operating a sophisticated sound board and video control panel. The lighting was perfect. The fonts and graphic design were impeccable.

How do a dozen people (eleven, because I don’t count) support the maintenance of an aging church that big, with that kind of infrastructure? They didn’t even take a collection.

When I chatted a bit with the priest after the service, it became clear that the church had fallen into serious hardship even within the last few decades, and he had brought the 5:00 congregation—the lively one, with all of the energy (and, presumably, money)—with him from elsewhere only seven years ago.

What he also did, however, was to create a space in the revitalized ministry of the church in which to house the historical liturgy, even though most of his flock completely ignores it.

In other words, he had done for the old prayer book what architects and archaeologists had done for St. Mary’s Charnel House a few blocks away—not even a decade earlier. In some sense, he had done what I was afraid would happen with our time in Britain, and before leaving his church I had sincerely thanked him for doing it. If he had not kept that place in the church day for that service—if he had let the old words grow organically into the present—the old words would undoubtedly have disappeared into watery modernized ones. There needed to be a place set aside, even if that meant people walked right on by it.

So when I walked away from the charnel house and saw the house where I had finally heard the “comfortable words” of Thomas Cranmer’s prayer book, I had some thinking to do.

It’s okay, I decided. It’s okay if the knowledge and wisdom gained over this semester is mostly contained in final portfolios that the students themselves will never read again. It’s okay to blog for oblivion. It’s okay for two reasons.

First, the acts of reading, writing, and thinking that my students have done—if those acts have been at all meaningful—will continue to shape our unfolding present whether we want it to or not. We’re all better read now. We’re savvier travelers. We have better instincts in some things. As my mom used to say all the time: “Education is never wasted.”

The kind of organic growth I want to happen is in fact already happening. Some students have endured some of the most difficult moments of their lives on this trip. They’ve written about those experiences in a “Traveler’s Tale” assignment, which is accompanied by an “Author’s Statement” explaining why the chose to tell the story in the way they did. I’ve noted with deep joy not one but two stages of development in some students, one in the tale itself and another in the statement. They tell these tales with a sense of humor, with the detachment of hindsight; tragedy becomes comedy (or at least much less tragic than it was in lived experience). And in their statements they recognize that this has happened, putting themselves at a second remove.

Second, it’s okay to pocket the past because there are always the elephants—those things that stop us in our tracks and move us toward the rediscovery of something long forgotten. I take comfort in the idea that, for instance, a student five years from now will hear a reference to George Herbert and say, “Hey, I know that name… wait, I marked up a whole poem of his with that group back in Liverpool. That was actually pretty cool.” And maybe the volume will then be rescued from a shelf, with the notes still in it.

Or, more realistically, they’ll find themselves in one of life’s steep valleys and say, “Wait, I’ve been here before. I was here in Liverpool.” And they’ll re-read their Traveler’s Tale—or they’ll simply remember how they told and re-told that tale—and they’ll have thrown themselves their own rescue line, because they know from experience that the tragedy of the moment is not the final word.